This article is part of a series.

View all 3 parts

- Part 1 – Beginning MySQL for Data Analysts

- Part 2 – This Article

- Part 3 – Setup a Local MySQL Database

Welcome back! Alright, now we know how to connect to a remote server from within MySQL Workbench, let's start writing some queries.

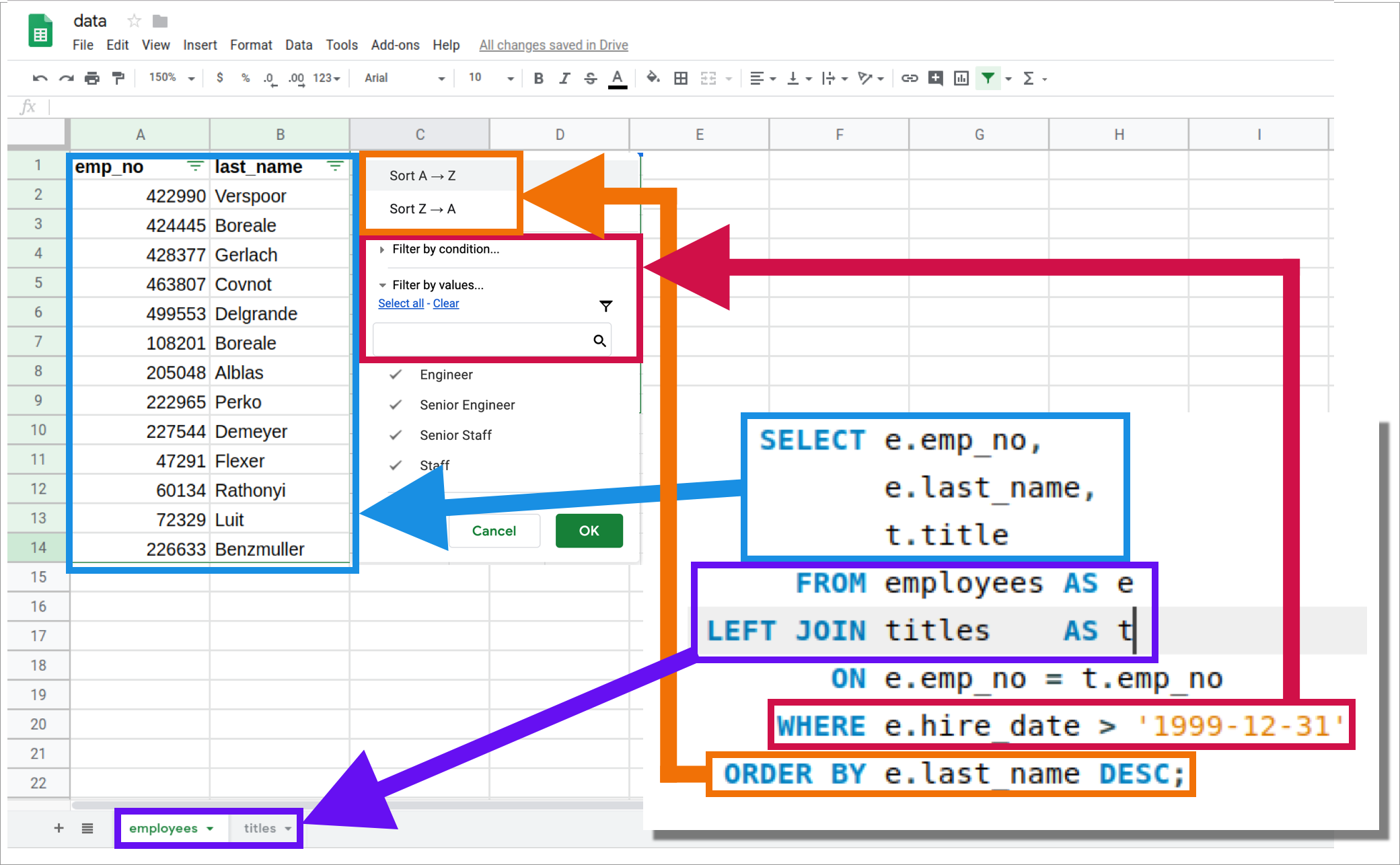

Here's a common SQL query:

SELECT e.emp_no,

e.last_name,

t.title

FROM employees AS e

LEFT JOIN titles AS t

ON e.emp_no = t.emp_no

WHERE e.hire_date > '1999-12-31'

ORDER BY e.last_name DESC;

This query produces the following table when run on our

employees

database.

| row_num | emp_no | last_name | title |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 47291 | Flexer | Staff |

| 1 | 60134 | Rathonyi | Staff |

| 2 | 72329 | Luit | Staff |

| 3 | 108201 | Boreale | Senior Engineer |

| 4 | 205048 | Alblas | Senior Staff |

| 5 | 222965 | Perko | Senior Staff |

| 6 | 226633 | Benzmuller | Staff |

| 7 | 227544 | Demeyer | Senior Staff |

| 8 | 422990 | Verspoor | Engineer |

| 9 | 424445 | Boreale | Engineer |

| 10 | 428377 | Gerlach | Engineer |

| 11 | 463807 | Covnot | Engineer |

| 12 | 499553 | Delgrande | Engineer |

When the data are presented like this, it appear similar to our traditional Excel spreadsheet, right?

Let's compare the SQL query and a spreadsheet.

Now, here in a few weeks when you are SQL-writing-machine you'll notice this analogy between Excel and a SQL query breaks down. But for now, let the above image comfort you in knowing the core functions of SQL are similar to those of a spreadsheet. And you know these spreadsheet functions well .

- Selecting columns

- Filtering columns and rows

- Ordering rows

- Combining data sets

However, SQL has a lot of superpowers an Excel spreadsheets doesn't. Of course, the tradeoff is you must leave behind the comfort of a graphical user interface. But don't let it scare you off--it only takes a 3-4 months to get used to, but then you'll realize how much those graphical interfaces have been chaining you down.

Alright, back to the queries. Let's take a look at the different parts of the query above.

SELECT

The

SELECT

statement is how you choose what turns up in the results section. If don't put something in the

SELECT

area, then you will not get anything. It is often used to retrieve data, called fields, from one or more tables within a database.

Select Area

You may ask, what is the "SELECT area." It is everything between the word

SELECT

until

FROM

.

SELECT -------------------------------

-- ALL THIS IS THE SELECT AREA

-------------------------------

FROM

Select Fields

There are two different ways to

SELECT

fields you want to get results from. You can use the

*

, which means "everything." Or you can list the field names you want returned. Each item you put in the

SELECT

area should be followed by a comma, unless it is the last item.

For example:

SELECT emp_no,

last_name,

title

...

The code above requests three different fields be returned in the result set:

emp_no

,

last_name

, and

title

.

Or

SELECT *

...

Returns every field, in every table listed.

I should point out, if you forget a comma it can get messy. Often, the SQL server will send an error message, but not always . As we will see in a moment.

Select Calculations

The

SELECT

does more than retrieve data from tables within a database. It can also perform on-the-fly calculations, such as

SELECT 1 + 1,

2 *25,

55 / 75,

This should return the following:

| 1 + 1 | 2 *25 | 55 / 75 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 50 | 0.7333 |

FIELD

A field in SQL is similar to the column in a spreadsheet. It contains data of the same type on every row (more on datatypes later). Fields may be referenced throughout a SQL query, but for them to show in the query results they must be included in the

SELECT

area--as we went over in the "SELECT" section above.

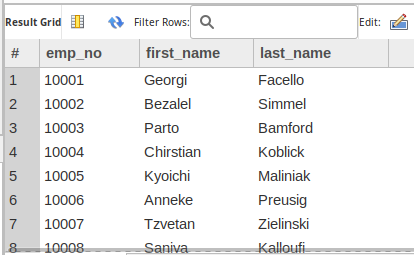

SELECT emp_no,

first_name,

last_name

FROM employees

Ambiguous Field List

The above query works. However, try running the following query, which includes two tables.

SELECT emp_no,

first_name,

last_name

FROM employees

LEFT JOIN titles

ON employees.emp_no = titles.emp_no

You get any results? Me either. Only an error message from the database stating:

Error Code: 1052. Column 'emp_no' in field list is ambiguous

This is because both the

employees

and

titles

table have a field named

emp_no

and the SQL program can't figure out which you want.

To solve this, we add the table name plus

.

to the front of each field name. This will tell the SQL program from which tables we would like to field to come from--leaving no ambiguity. Computers

hate

ambiguity.

Let's run the query again with table names.

SELECT employees.emp_no,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees

LEFT JOIN titles

ON employees.emp_no = titles.emp_no

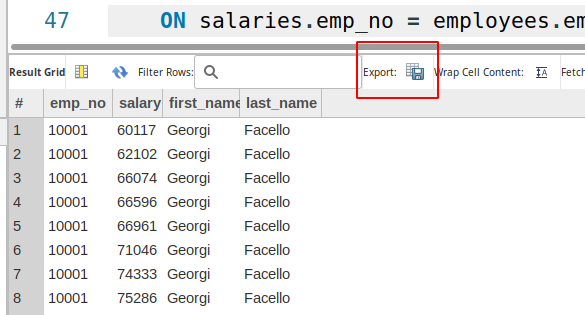

This time we get the results we expected, without error.

Building on this, a good SQL coder will always prepend the table name to the front of the query, whether it's required or not. This prevents future mistakes.

For example, let's say you wrote this code:

SELECT emp_no,

salary

FROM salaries

And your code was put into production (a term meaning put to use by your business) then a year later another coder added a second table to the query without critically looking at the query as a whole (something a bad SQL coder forgets to do).

The new query looks like this:

SELECT emp_no,

salary,

first_name,

last_name

FROM salaries

LEFT JOIN employees

ON salaries.emp_no = employees.emp_no;

Try to run this query. You will find the same

field list is ambiguous

error as we saw earlier.

The deeper lesson here is: A good coder is like a defensive driver; they code in a way it expects others to be reckless.

Back to the example above, if we include the table in the field names, then it doesn't matter if a reckless coworker adds another table.

SELECT salaries.emp_no,

salaries.salary,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM salaries

LEFT JOIN employees

ON salaries.emp_no = employees.emp_no;

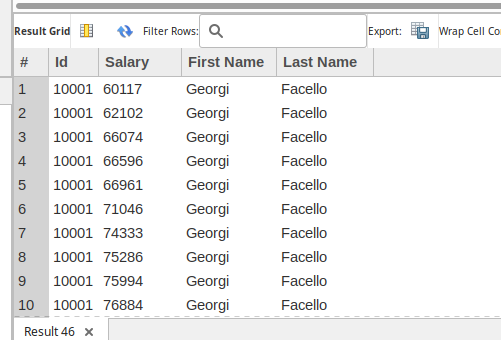

Field Aliases

Often you will want to export your results into a CSV to send to someone. You may have noticed when you execute a query SQL returns the results in a neat spreadsheet. I don't know if I've mentioned it, but you can export these results in a CSV by hitting the little disk button above the results.

However, you may not like the machine formatted column names. I mean, don't get us wrong, we're nerds! We read machine friendly words fine, but our bosses don't.

Well, MySQL has a built in command allowing you to rename fields (and more) on the fly. This command is

AS

and is seen in the query below written to rename the column names.

SELECT salaries.emp_no AS Id,

salaries.salary AS Salary,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM salaries

LEFT JOIN employees

ON salaries.emp_no = employees.emp_no;

Now the column headers have "boss-friendly" names.

You've probably noticed the first two aliases are written without quotation marks and the second two are surrounded by them. The SQL program can get confused by spaces, so we wrap the new name in

"

marks. When the SQL program sees these marks, it says to itself, "Oh, I bet the user is going to have one of those fancy human names, I'm going to assume everything between the first quotation mark and the next one I find is all one fancy human word. Silly humans."

A more technical term for someone inside quotations marks is a literal constant. However, programmers know them as "strings." It's probably b

Don't Lose Your AS

Go ahead and try to run this query:

SELECT emp_no

first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees;

Did you run it? Anything jump out as weird? You don't really run it did you? Go run it, I'll wait.

Ok, you'll see something like this:

| first_name | last_name |

|:-----------|:----------|

| 10001 | Facello |

| 10002 | Simmel |

| 10003 | Bamford |

| ... | ... |

Super weird right? There are only two columns and it seems like the column names are jumbled up. That's exactly what's happened. It's due to a missing

,

right after the

emp_no

. This is a result of something in SQL I think is silly--you can omit the

AS

keyword between a field and its alias.

Meaning, we could rewrite the query from earlier where we showed alias use like this:

SELECT salaries.emp_no Id,

salaries.salary Salary,

employees.first_name "First Name",

employees.last_name "Last Name"

FROM salaries

LEFT JOIN employees

ON salaries.emp_no = employees.emp_no;

But, the first time you miss a comma you'll be asking, "Why!? Why does MySQL allow this!" I'm not sure, but we have to deal with it. This is why I ask you

always

include the

AS

keyword. Again, you are helping prevent bugs before they happen.

FROM

As you've already seen, the

FROM

command tells SQL where on the database it should look for data. If you don't specify a table in the

FROM

clause, then the SQL program acts if it doesn't exist, and will not be able to find the fields you request.

SELECT *

FROM employees

LEFT JOIN departments

ON employees.emp_no = departments.emp_no

In the next article we are going to talk about

JOINS

, they are an extension to the

FROM

clause of a query, but, they deserve their own article. Right now, look at the

LEFT JOIN

as an extension of the

FROM

clause. A join tells the SQL program, "First look in the employees table, then, check in the departments table,

if

there is a relationship with the employees table."

Like I said, we will review

JOINS

thoroughly in the next article.

Table Aliases

Like we could give fields nicknames, called aliases, we can do the same with table names. However, this is usually done for a different reason: To save on typing.

One of the primary reason bad coders don't write out the table names (not you , you're going to be a good coder) is it adds a lot more to type. You may say, "Well, that's just lazy." It is, but it's smart-lazy--also know as efficient. And efficiency is something you want to strive for in your code and coding .

Let's look at an example from earlier.

SELECT salaries.emp_no AS Id,

salaries.salary AS Salary,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM salaries

LEFT JOIN employees

ON salaries.emp_no = employees.emp_no;

This query could be rewritten by using table aliases and save a lot of typing. It's probably best to show you.

SELECT s.emp_no AS Id,

s.salary AS Salary,

e.first_name AS "First Name",

e.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM salaries AS s

LEFT JOIN employees AS e

ON s.emp_no = e.emp_no;

Execute this query and compare its results to the query without table aliases. You will find the results are exactly the same. Moreover, this rewrite has saved 45 keystrokes. You may think, "Eh, not much." Well, this is a small query. Imagine writing queries twice this size all day long. Your savings are worth it--may the time for an extra cup of coffee (or pot, in my case).

It is also easier for the human brain to comprehend--at least, once you've been reading SQL for awhile. Your brain will understand

e

and

employees

the same, but it doesn't have to work as hard to understand

e

.

In short, good coders use table aliases.

ORDER BY

In spreadsheets there will usually be a way to sort your data. Often your options will be based on a column's contextual order. If the data are numbers it will be low-to-high, or high-to-low, respectively. If it's text then your choice will probably be alphabetical, either A-Z to Z-A. And if it's a date, then it will be first-to-last, or last-to-first. Each of these order types share a commonality, they value either goes to a low-values to high-values, or high-values to low-values. These types of ordering are known as ascending and descending, respectively.

In SQL, there are two types of

ORDER BY

s,

ASC

and

DESC

, for ascending and descending. They operate a bit different than most spreadsheet applications. They still order data by low-to-high or high-to-low, however, when you apply an

ORDER BY

it affects the entire result set. When a field is targeted by an

ORDER BY

all other fields on the same row are ordered along with the targeted field.

Enough words. Let's take a look at some examples:

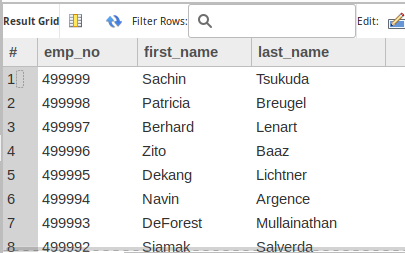

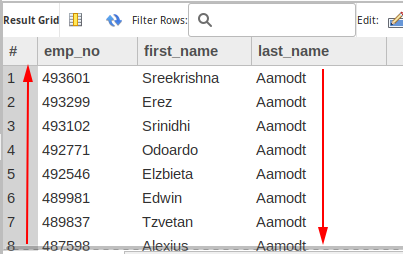

DESC

SELECT employees.emp_no,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees

ORDER BY employees.emp_no DESC

ASC

SELECT employees.emp_no,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees

ORDER BY employees.emp_no ASC

One note about

ASC

, if you do not specifcy what type of

ORDER BY

then it will default to

ASC

.

For example, this query will provide the exact same results as the one above:

SELECT employees.emp_no,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees

ORDER BY employees.emp_no

Most of

ORDER BY

is used for humans, making it easier to find whether your data were returned correctly. However, there are instances where

ORDER BY

will actually change the results of your queries, but it will be awhile before we get into those sorts of queries.

Later, we're going to start working on making our queries efficient and fast, but now I'll state:

Make sure you need your results ordered before you

ORDER BY

.

It can be hard work for SQL program to order your results, which translates to longer execution times. Something you will want to avoid if you are trying to write a query for speed (which you will when writing code for production software).

Multiple Column Sort

SQL can also do multiple-field sorts. This works by sorting by the first field in the

ORDER BY

and where there are ties, then sort by the second field.

For example:

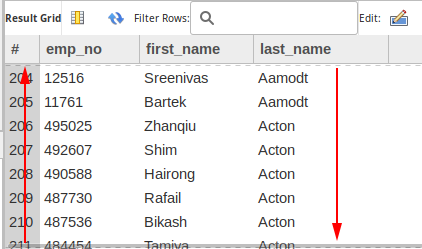

SELECT employees.emp_no,

employees.first_name,

employees.last_name

FROM employees

ORDER BY employees.last_name ASC, employees.emp_no DESC

"Aamodt" is the first employee in the

last_name

field when the

ORDER BY

is set to

ASC

, however, there are many "Aamodt"s in this table. This is where the second

ORDER BY

comes in. The second

ORDER BY

is set on the

emp_no

field and is

DESC

, this is why all the numbers start at the highest values and move towards the lowest. Of course, when the the

last_name

value changes the

emp_no

order will restart, still moving from highest to lowest.

Alright, let's move on. Just remember,

ORDER BY

is extremely useful for humans, but it makes it slower for computers to process. Therefore, when you write a query, consider your audience.

WHERE

The

WHERE

clause of a SQL query is a filter. Simple as that. It further limits your results. And it is probably the second most important portion of a query, next to the

FROM

clause. Reducing your results not only help you find what you need, it also makes it easier on the computer to find the results.

Though, before we get into more detail let's take a look at an example:

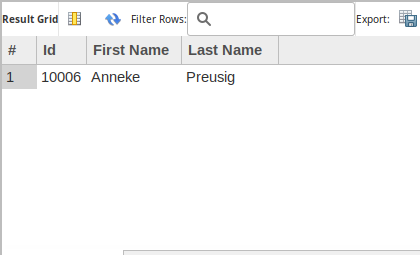

SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM employees

WHERE employees.emp_no = 10006

ORDER BY employees.emp_no, employees.first_name

This returns a single record, which makes sense. We told the SQL program we want

emp_no

,

first_name

,

last_name

from the

employees

table where the

emp_no

is equal to

10006

.

But, let's also look at the

Database Message

| Time | Action | Message | Duration / Fetch |

|---|---|---|---|

| 07:35:17 | SELECT employees.emp_no, employees.first_name, employees.last_name FROM employees ORDER BY employees.last_name ASC, employees.emp_no DESC LIMIT 0, 1000 | 1000 row(s) returned | 0.152 sec / 0.0035 sec |

| 07:48:56 | SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id, employees.first_name AS "First Name", employees.last_name AS "Last Name" FROM employees WHERE employees.emp_no = 10006 ORDER BY employees.emp_no, employees.first_name LIMIT 0, 1000 | 1 row(s) returned | 0.0036 sec / 0.0000072 sec |

Notice how our query for one result took

much

less time than the query for a 1,000 results? I'll cover this more later, but felt it was import to point out now. Using the

WHERE

clause to limit the data to only what you need will greatly increase the efficiency of your query.

Ever been to a cheap buffet with the sign posted on the sneeze-guard reading: "Take only what you will eat!!!" Well, imagine your SQL database has the same sign--you choose what you need with the

WHERE

clause.

Ok, enough on efficiency for now, let's focus on how the

WHERE

clause will allow you to get the results you are after.

In queries we've written earlier, we've received every row on the database, from every table included in the

FROM

clause. Now, we are narrowing the results down to those of interest.

This can also be done with strings (text inside of

"

marks).

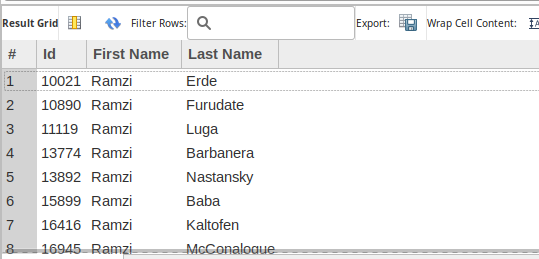

SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM employees

WHERE employees.first_name = "Ramzi"

ORDER BY employees.emp_no, employees.first_name

But what if we want to include multiple different employees, but not all? That's where

IN

comes...in.

IN

The

WHERE

clause can be followed by the

IN

keyword, which is immediately followed by a set of parentheses; inside the parentheses you may put list of values you want to filter on. Each value must be separated by a comma.

For example:

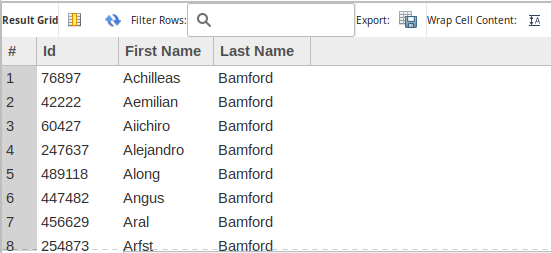

SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM employees

WHERE employees.last_name IN ("Bamford", "Casley", "Benveniste")

ORDER BY employees.last_name ASC, employees.first_name ASC;

This can also be done with numbers

SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM employees

WHERE employees.emp_no IN (422990, 428377)

ORDER BY employees.last_name ASC, employees.first_name ASC;

Greater and Less Than

If the field you are using is numeric data, then you can also use the

>

,

<

,

<=

, and

>=

comparisons.

SELECT employees.emp_no AS Id,

employees.first_name AS "First Name",

employees.last_name AS "Last Name"

FROM employees

WHERE employees.emp_no > 40000

ORDER BY employees.emp_no, employees.first_name;

If you aren't familiar with the equalities, here's a breakdown.

- "> 5000" will find all values which come after 5000, but does not include 5000 itself

- "< 5000" will find all values which come before 5000, but does not include 5000 itself

- ">= 5000" will find all values which come after 5000 including 5000 itself

- "<= 5000" will find all values which come before 5000 including 5000 itself

Closing

Whew, these are the basic of a SQL query, but, it's just the beginning. There are many more parts to SQL queries, such as

AND

,

OR

,

<>

,

!=

,

JOIN

, functions,

UNION

,

DISTINCT

--we've got a lot more to do. But! No worries, you've totally got this.

Don't believe me? Don't worry, I'm going to let you prove it to yourself. Let's do some homework! :)

Homework #1

The following homework will have you take the query provided and modify it to return the described result. Once all queries are completed, fill free to email the queries to me and I'll "grade" them for you.

For questions #1-6 use the following query:

SELECT *

FROM employees

LEFT JOIN dept_emp

ON employees.emp_no = dept_emp.emp_no

LEFT JOIN departments

ON dept_emp.dept_no = departments.dept_no

LEFT JOIN titles

ON employees.emp_no = titles.emp_no

LEFT JOIN salaries

ON employees.emp_no = salaries.emp_no;

- Question #1 -- Modify the above query to use table aliases instead of full table names.

-

Question #2 -- Modify resulting query to

only return results for

emp_no,first_name,last_name,dept_name,salary. - Question #3 --Modify resulting query to *rename the fields to the following "Employee #", "First Name", "Last Name", "Department #", and "Salary".

- Question #4 --Modify resulting query to list employees by their salaries; order them lowest salary to the highest.

- Question #5 --While keeping the lowest-to-highest salary order, modify resulting query to list the employees in alphabetical order by their last name where their salaries are tied.

- Question #6 -- Modify resulting query to only provide clients who have make over 50,000

For questions #7-10 use the following query:

SELECT *

FROM employees AS e

LEFT JOIN dept_emp AS de

ON e.emp_no = de.emp_no

LEFT JOIN departments AS d

ON de.dept_no = d.dept_no

LEFT JOIN titles AS t

ON e.emp_no = t.emp_no

LEFT JOIN salaries AS s

ON e.emp_no = s.emp_no

- Question #7 -- Modify the above query to only return results for those with the first name "Yishay", "Huan", or "Otmar"

-

Question #8 -- Modify resulting query to

to also show only their

first_name,last_name, andsalary. - Question #9 -- Modify resulting query to to also show what departments they work in .

- Question #10 -- Modify resulting query to also show their hire date .