This article is part of a series.

View all 13 parts

- Part 1 – HMIS, R, and SQL -- Introduction

- Part 2 – HMIS, R, and SQL -- Basics

- Part 3 – Preamble to Mixing R and SQL

- Part 4 – HMIS, R, SQL -- Work Challenge One

- Part 5 – Read and Write CSVs in R

- Part 6 – This Article

- Part 7 – Filter to Most Recent HUD Assessment

- Part 8 – HMIS, R, SQL -- Work Challenge Two

- Part 9 – Comparing Values in R and SQL

- Part 10 – Working with R Excel Libraries

- Part 11 – HMIS, R, SQL -- Work Challenge Three

- Part 12 – HMIS, R, SQL -- Work Challenge Four

- Part 13 – SQL CASE and R Paste

Mixing R and SQL is powerful. One of the easiest ways to implement this combination is with the R library SQLdf.

If TL;DR, skip to

Coerce Date Types into Strings before Passing to SQLdf

at bottom.

SQLdf

The power of SQLdf comes from its ability to convert dataframes into SQLite databases on the fly. To the user, it doesn't appear like anything special is going on, but under the hood R is working together with a SQLite client to create a table which can be queried and manipulated with ANSI SQL calls.

For example,

dataFrame1 <- read.csv(pathToData)

library("sqldf")

dataFrame2 <- sqldf("SELECT FirstName FROM dataFrame")

These three lines do a lot. It loads data from a CSV, loads a library of functions for convert R dataframes into SQLite databases, and then the

sqldf()

function call does two things at once. It converts the R dataframe into a SQLite database and then queries it for the FirstName column.

If we were to assume the dataFrame1 variable contained data like this:

| PersonalID | FirstName | LastName |

|---|---|---|

| B7YIOJIGF9CDP6FV7TANQXLMQRMBTVTB | Bob | Person |

| ASGJ4F95HS85N39DJ12AJB094M59DJ45 | Jane | People |

Then the

dataFrame2 <- sqldf("SELECT FirstName FROM dataFrame)

will create a variable called

dataFrame2

which contains the FirstName column from dataFrame1

| FirstName |

|---|

| Bob |

| Jane |

And this is how we will shape our data in the R-SQL way.

Datatypes

One of the most important things a human can learn about computers is something called datatypes. When computers process information they need a little help from humans in attempt to understand what to do with the information. For example, what do these numbers mean to you?

76110, 444-325-7645, 10/24/1980

Most humans (at least in the United States) will know the first number is a ZIP code, the second a phone number, and last date. Humans know this because our brains have learned how to discern from context. In the case of the ZIP code, it's exactly 5 numbers, the phone contains dashes at at exact places, and the date contains slashes in the exact spot we'd expect of a date.

Unfortunately, computers have a little more difficulty with this. Most computers are smart enough now days to know the phone number and date of birth, but the ZIP code will confuse the heck out of a computer.

A computer's initial reaction in seeing the ZIP code is, "Oh, you mean 76,110. That's a big number." When really, this number represents a geographic location.

Ok, let's make this more relevant to HMIS work. The way to help a computer understand what numbers are representing is by telling the computer what type of data a particular column is. This is known as a datatype. For us, we really only deal with a few datatypes, but their are hundreds of thousand of datatypes.

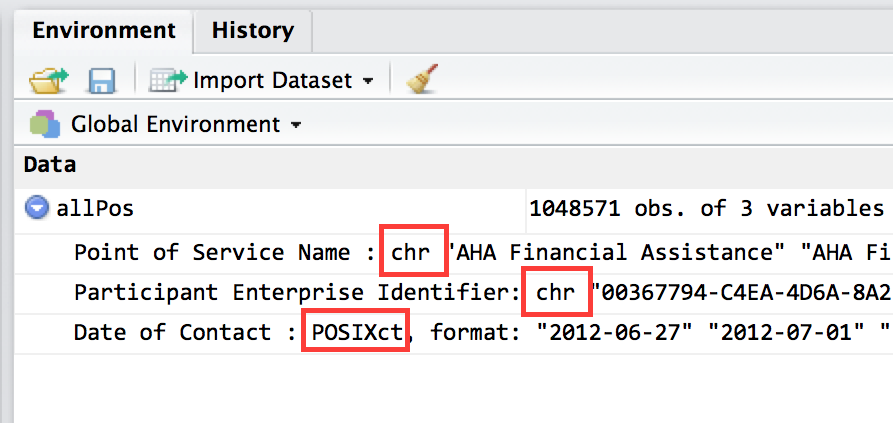

In R you can see what datatype a column of your dataframe is by clicking the blue button next to the dataframe name in the Global Environment variables.

We will be dealing with the following:

- Dates (called "POSXct" in R)

- Strings (called "chr" in R)

- Numbers

- Factors

Of course, every programming language can calls these datatypes by different names, thus, furthering confusion. (I mean, c'mon, programming is simple enough as it is--we've got to make it a little challenging.)

Dates

Date datatypes usually look like this:

10/24/1980

But it can come in many different formats. It's probably best to differentiate between datatype and data format . A data type describes how the information should be used--it's important for a computer. Data format describes how a computer should display information to the human--therefore, it's useful for a human.

An example of different formats of the same data:

10/24/1980

1980-10-24

102480

Ok, back to the date datatype. It is used when dealing with dates. By declaring a variable as having a date datatype, it is telling the computer whatever we put into that variable to interpret as a date. Simple enough.

Strings

When we talk about string we aren't talking about fuzzy things kittens chase. A string datatype is a series of characters (one part of a string) strung together. Anything can be a string. They are probably the most important datatype, since they can tell a computer to look at a number and see something else. Confused? Let's look at some examples.

We tell a computer data is a string is by putting it in double quotes

"this is a string"

or single quotes

'this is also a string'

.

Here's an example of assigning a string in R:

myFirstString <- "this is a string"

Great! But what can we do with it? Well, a lot.

Let's say we wanted to pass a path of a file to a

read.csv()

function. We could do so by providing the path as a string.

dataFrame <- read.csv("/Users/user/Downloads/Client.csv")

The above will load the Client.csv file located at the

/Users/user/Downloads/

directory--the computer knows how to read the path because it's a string.

But why are strings so important? Well, they allow us to tell a computer to override its basic instinct and view a piece of data as something other than what the computer would guess it is.

Returning to the ZIP code.

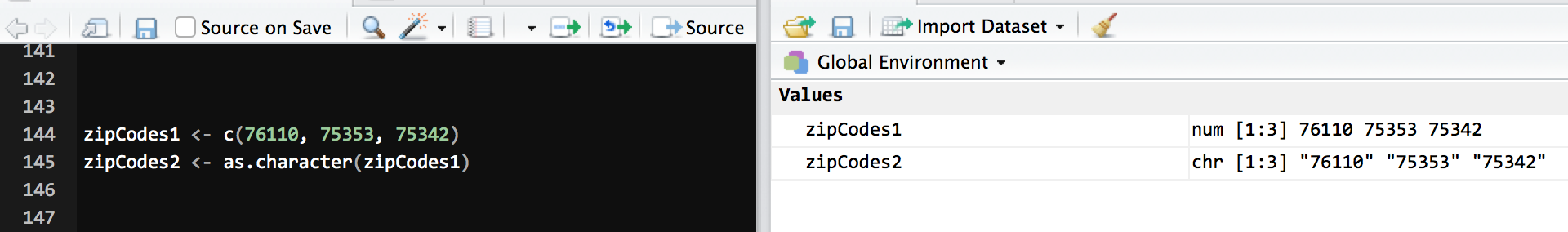

notAZipCode <- 76110

myZipCode <- "76110"

These variable assignments may seem to be exactly the same, however, the first one creates a variable as a number, but the second tells the computer, "This is a not a number, it is something else--please don't pretend to understand it. I'll tell you exactly what to do with it later."

Numbers

Number datatypes are easy. It's pretty much how a computer tries to look at all data you provide it. One important characteristic about numbers, you can have the computer perform math functions on numbers, which you couldn't on strings.

dataframe1 <- 12 * 12

datafram2 <- "12" * "12"

Above,

dataframe1

will contain 144 after being executed. But if the second line is attempted to be executed the computer will freak out, "This is a string! I can't add strings! You told me you'd tell me what to do with them..."

Factors

Factors are a special datatype in R. Most of all the variables we load in R will start out as factors. Essentially, factors are categories of data.

Red,

Orange,

Green,

Blue,

Indigo,

Violet

Is an example of factors. They are categories of data. The important of factors will become more evident as we work through these tutorials in R.

If you don't understand factors, it's cool. Just think of them as strings. However, if you don't understand strings, please ask any questions in comments below. Understanding them is critical to working with SQLdf.

SQLdf and Datatypes

Anytime you mix two different languages it pays to be careful about meaning. As I learned once by talking about pie as something I liked--come to find out, it was funny to Hispanic friends who were learning English. (Apparently pie is Spanish for foot?)

When mixing R and SQL we must be careful about how the two languages look at the datatypes. In R it sees dates as a

POSXct

datatype (this is essentially fancy

date

datatype.

Would you like to know more

?)

Well, this is all fine and dandy, but when we pass commands from R to SQL it is all passed as a string.

dataFrame2 <- sqldf("SELECT * FROM dataFrame1")

Notice

SELECT * FROM dataFrame1

is all in quotation marks? This turns it into a string then it passes it SQLite, which is hidden to us.

If all this is a bit overwhelming, no worries. Bookmark this page to refer back to later. Just remember the following:

Date columns must be converted into a

chr

datatype

before

passing it to SQL. How to we convert datatypes? It's pretty darn simple. We use something called data coercion.

Coercing Data Types

Let's go back to that ZIP code and number example. Let's say the computer reads all your ZIP codes from a file as a number. This happens a lot, since to the computer that's what it looks like--so it guesses that's what you are going to want.

But no, we want those ZIP codes to be strings. To do this, we can get a particular column from a dataframe by writing the name of the dataframe then

$

then the name of the column. For example,

datafram$zipCodes

will return only the column

zipCodes

from dataframe.

Alright, now we have a way to select one column from our dataframe we can attempt to convert that one column's datatype. To do this use the

as.character()

command.

dataframe$zipCodes <- as.character(dataFrame$zipCodes)

This will convert the zipCode column from a number into a string, then, it assigns it back to the column zipCodes. Boom! We've told the computer to stop trying to make a ZIP code a number. Instead, treat it as a string. And with that, we will tell the computer later how to use ZIP codes.

Coerce Date Types into Strings before Passing to SQLdf

Ok, now for the reason for this entire article. Before passing any dates to SQLdf we need to first convert them to strings. Otherwise, SQLdf will try to treat them as numbers--which will cause a lot of heartache.

For example, a Client.csv file should have a

DateCreated

column. This represents the date a case-manager put the data into HMIS. The data should look something like this:

| ... | DateCreated | DateUpdated |

|---|---|---|

| ... | 10/23/14 0:01 | 4/23/15 15:27 |

| ... | 5/22/13 9:23 | 10/15/16 1:29 |

| ... | 6/3/15 19:22 | 3/17/17 21:09 |

Let's try to get all of the clients who've been entered after 10/01/2014.

dataFramContainingDates <- read.csv("/Users/user/Downloads/Client.csv")

datesEntered <- sqldf("SELECT * FROM dataFramContainingDates WHERE DateCreated > '2014-10-01'")

The above code should provide every column where DateCreated date is greater than 2014-10-01. But, instead, it will result in an empty dataframe. Waaah-waah.

Essentially, this is because SQL is comparing a number and a string. It freaks the computer out.

Instead, we should convert the

DateCreated

column to a string instead of a date. Then, SQL will actually convert it from a string to a date.

Confused? Imagine me when I was trying to figure this out on my own.

Ok, so, the take away? Before passing any dates to SQL convert them to strings.

dataFramContainingDates <- read.csv("/Users/user/Downloads/Client.csv")

dataFrameContaingDates$DateCreated <- as.character(dataFrameContaingDates$DateCreated)

datesEntered <- sqldf("SELECT * FROM dataFramContainingDates WHERE DateCreated > '2014-10-01'")

By using the

as.character

function to convert the

DateCreated

column to a string and then assigning it back to the dateframe, it sets SQL up to do the date comparisons correctly. Using the dateframe from above, this should result in the following table:

| ... | DateCreated | DateUpdated |

|---|---|---|

| ... | 10/23/14 0:01 | 4/23/15 15:27 |

| ... | 6/3/15 19:22 | 3/17/17 21:09 |

Confused as heck? Feel free to ask questions in the comments below!